6.4 Bodies, health and disease

Life was precarious in early modern Europe and often all too short. Between one-tenth and as many as a half of all children died before their tenth birthday. Epidemic diseases could devastate communities. A single plague outbreak in seventeenth-century Amsterdam killed up to one-sixth of the population; the same disease killed over four-fifths of the people of Santander in Spain (Kamen, 2000, p. 25). For much of the population, any illness that prevented them from working for even a short time meant a slide into poverty, while injuries such as broken limbs could result in permanent disability.

In early modern Europe, many people understood how their bodies functioned by using theories devised in ancient Greece and Rome by scholars such as Hippocrates (c.460 BCE–375 BCE) and Galen (129–199 CE). The important components of the body were thought to be four fluids, or humours: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. When these fluids were balanced, the body was healthy. When there was some form of imbalance – an excess of one or more fluid, or a blockage in their flow around the body – illness occurred. This could be caused by an inappropriate diet, environment or lifestyle. Although this idea seems very strange to us, it was based on observation: when ill the body often ejects fluids such as vomit or phlegm. Under the humoral system, this was interpreted as the body trying to heal itself by getting rid of bad or excess fluids.

Sickness in early modern London

What kinds of illnesses did people suffer in the early modern period?

Activity 9 A bill of mortality

This should take around 10–15 minutes

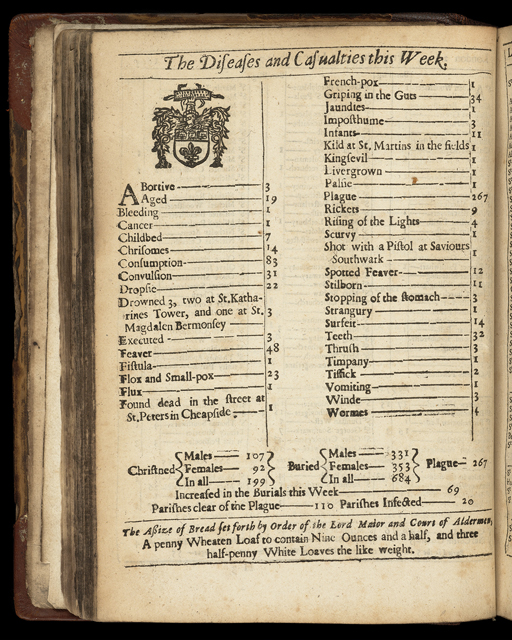

Look at this bill of mortality (a record of deaths) from London for one week in 1665 (Figure 7). What diseases do you recognise?

Discussion

There are a few names here that you might recognise, including cancer, fever (spelled ‘feaver’), smallpox, plague and scurvy. Some of the diseases listed, such as convulsions, ‘griping in the guts’ (stomach pains or cramps) or ‘teeth’, seem to be unlikely causes of death. Bills of mortality are a reminder of how difficult it can be to understand what went on in the past.

Of course, people also suffered from less serious complaints, such as coughs, colds and stomach upsets, and children caught infectious diseases such as measles.

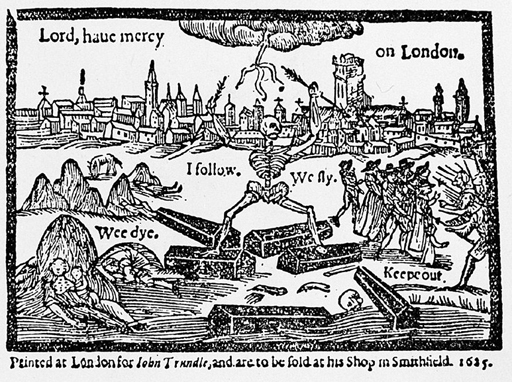

To cure disease and restore the balance of humours, people adjusted their lifestyles, ensuring that they got enough sleep and exercise and avoided eating too much of one type of food. Medicines provided a more immediate means of adjusting the humoral balance by causing some form of evacuation from the body, and people readily swallowed purges (which caused diarrhoea) and emetics (which induced vomiting). Bloodletting was a popular cure, used for many ailments. Faced with epidemics, when many people fell ill at the same time, communities applied collective remedies, isolating infected people away from the healthy, using bonfires to purify the air and saying prayers to invoke divine help (Figure 8).

Medical treatment

Patients employed a wide range of practitioners to help them manage their health. At one end of the scale were physicians, trained in medicine at universities, who diagnosed illness by carefully observing symptoms and prescribed appropriate treatments. They charged high fees and were used by wealthy patients. A wider range of people employed surgeons, who dealt with injuries and other problems with the exterior of the body, and apothecaries, who prepared and sold medicines. Both surgeons and apothecaries lacked the thorough knowledge of the body possessed by physicians: they were not supposed to diagnose or prescribe, but in practice many did. At the other end of the scale was a variety of practitioners who lacked formal training: quacks or charlatans who sold remedies and carried out simple operations like removing teeth; midwives who helped deliver babies; and neighbours, friends and relations who might give out advice or medicines.

OpenLearn - Early modern Europe: an introduction

Except for third party materials and otherwise, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence, full copyright detail can be found in the acknowledgements section. Please see full copyright statement for details.

Except for third party materials and otherwise, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence, full copyright detail can be found in the acknowledgements section. Please see full copyright statement for details.